As I read posts from friends on Facebook, one lengthy piece caught my eye. It was from a woman who teaches violin, who many years ago was in the same Suzuki violin program as me. She wrote of her struggle to choose what to do, given the pressures of parents, teachers, friends, and her own inclinations.

The question she raised was “should I be a jack of all trades, or a master of one?” Her story continued with tales of her well-intentioned instruction, advice, and at times demands for her obedience. She wrote “I’ve traded security for freedom.” This resonated with me, as I thought back to my college experience.

In high school, I was encouraged to take an aptitude test to help me decide on a college major. One afternoon I took the test at the University of Tennessee where the test was proctored, and quickly muddled through the questions. Some time later, a letter arrived with the assessment that my aptitude was 99% engineer. Well, that makes it easy, I thought. My father was an engineer. I must be like him, in some way, and it looks like engineering school is in my future. I applied to a few universities, and ended up at Vanderbilt majoring in mechanical engineering.

There, amongst the many possible activities, I discovered the Vandyband. Having only one short semester of marching band in high school, I decided to join this band as my extracurricular activity. I can’t remember why. I suppose my positive experiences in high school came to mind, and I saw the band as a musical outlet and a social connection. For four years, I played my Olds Super 12 cornet in the band of about 120 students.

Small groups formed in the band. Some were organized, some were organic. One was the jazz band. In high school I was in the jazz band — I received the John Phillip Sousa award there. I tried to break into the Vanderbilt jazz band. I was secretly in love with a flautist and pianist, who played in the band, but she was not interested in me at all. So, my participation was both of unrequited love and a love of music. She was pictured in the 1982 Commodore annual as one of the “beautiful people.”

In time, the jazz band somehow morphed into a Dixieland band. I remember rehearsals in the basement of the band building, a former church on campus, where some of the band kids joined in this endeavor. I think we decided to be a Dixieland band after our first trip to New Orleans to accompany the football team competing with Tulane University. There, on Bourbon Street, we saw our assistant band director Herbie hoisting his trombone on the stage of a local bar, playing his heart out. He was not in the band on stage, but talked them into allowing him to join in. The joy he showed playing on that stage is a mental photograph I could pull up at any moment. I wanted that joy.

So, the Dixieland band continued rehearsing. We had one “gig” and I have no recollection of how we were chosen for it. We played in the big shopping mall, at 100 Oaks, one Saturday morning. We ran through a few classic charts, like “Frankie and Johnny.” A young lady who lived in a suite on the same floor as me in Carmichael Towers was there shopping, and she complimented my playing. Sadly, she was also not interested in me at all, having a very handsome boyfriend who regularly spent the night in her suite. But, her genuine compliment gave me confidence that I was somewhat musical.

Band life was obviously a big part of my college experience. One day I found myself at the band building, and the director, Howard “Zeke” Nicar (https://www.wku.edu/music/walloffame/index.php?memberid=5517), asked me a fateful question. The French department professor had stopped by. He needed a music director for the spring French department production. As I recall, his name was Professor Dan Church.

A small band was needed, and I was the leader of the Dixieland small band. Mr. Nicar for some reason thought I could do something that I had never even considered doing, and was not even aware I could do, creating a musical experience for others. “Zeke’s” confidence in me must have inspired me to accept the challenge, and so began a semester of intense musical focus. I was now the musical director of “Le Marathon.”

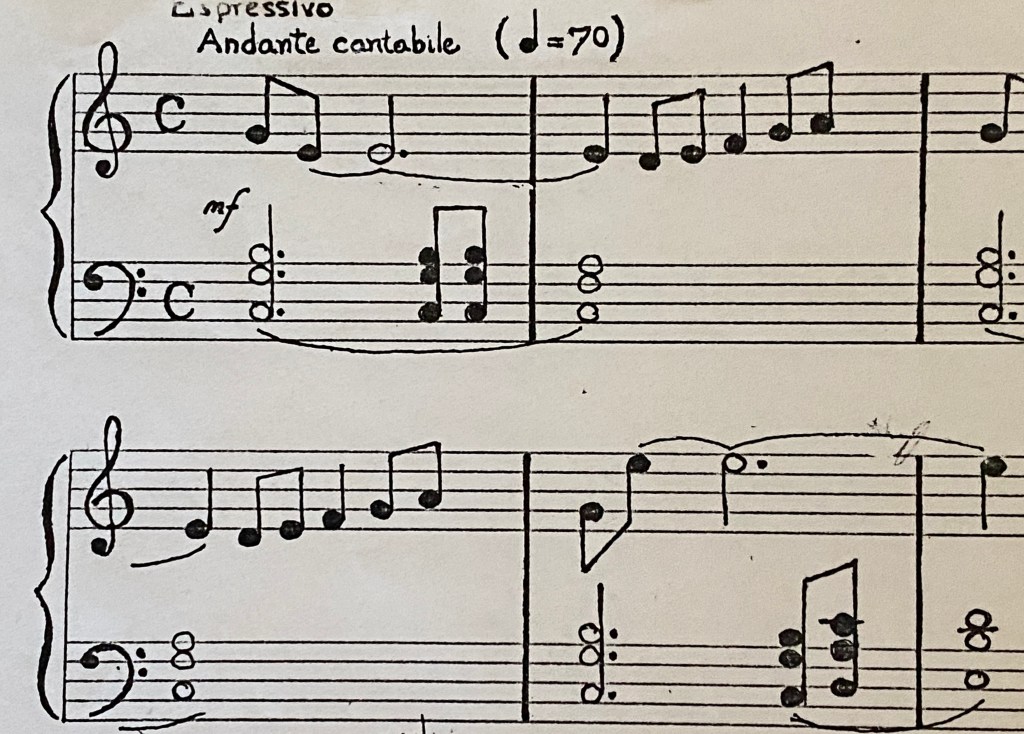

The French department play director gave me a cassette tape of a performance and a few sheets of music for the songs, as performed by the pianist. From that, I sat in the band building and somehow created charts for all the instruments in the band. From the cassette tape, I heard many instruments, and realized the Dixieland players were not quite enough for this sound stage. I recruited an alto sax, a tenor sax, a drummer, and even my little sister who was a dual threat on flute and violin. With the instruments chosen, I struggled to define the parts. There was a piano at the band building, and my Suzuki violin training kicked in. What I heard on the cassette became dots and lines on musical staff paper, as I heard the pitches over and over. I had the piano scores as a basis, but had to imagine the instrument parts from the sound. I realized that each instrument would need page after page of music, in the correct key for that instrument. E flat alto sax was a challenge to transpose. Why in the world did they create an instrument whose music was a major sixth higher than concert pitch?

There in the band building, day after day, I slowly handwrote the parts. I shaded in every solid note with the precision of an engineer’s draftsman. Measures were evenly spaced on the pages. Erasures were complete. The charts looked as close to printed music as I could make them.

I invited the band to run through the charts and made ready for a few performances. We sounded good. It was time to take the band to the Neely Auditorium for rehearsals. In this musical, the band was on stage, on a full riser in the back, while the actors actually ran on a fabricated track built out into the audience seats. It was, as entitled, a marathon performance, and for three acts, three able performers made lap after lap. One performer was older, balding, and overweight. One was tall, dark, and so very handsome. How the stars managed to run for the two hours of the show I’ll never know. As the actors circled the track, they spoke their dialog while jogging, until they needed to make some dramatic statement from the stage. On stage were four music stands for me. Two held the score notebook, and two showed the script in a three-ring binder. At some point, a cue would be spoken, as I followed the dialog with the script in French beside my band handwritten score. I conducted the band for songs the actors performed from those spoken cues. One show I was reading the script along with the actors, and saw the cue “Une drole de dance!” But I didn’t hear it…the actor had to restate the cue with some anguished emphasis, and I hurriedly raised my baton for a downbeat. At the end of the shows, I felt energized, rewarded, and fulfilled. I still have the conductor’s baton I purchased for the event. It remains the only tangible object from that exciting time of life. If only I could find it amongst all my memorabilia.

So, as they say, the rest is history. That semester of engineering school? I have no memory of it. I essentially did not go to class, did not do homework, and did not take tests seriously. It was my junior year, the first year of the real concentration of courses for mechanical engineering. Control systems theory was a blur. I hated dealing with matrix algebra. The Nyquist stability criterion? Who needs this? Thermodynamics? About the only thing that interested me there was the study of the car engine. All I could think about was “Le Marathon.” I may have a transcript of grades from that semester somewhere, but I was certainly put on academic probation for my low marks. My mom was not happy.

And like the real marathon, it all came to an end. My name was on the program, in French, as the “director de musique.” I had the cassette, the score, the parts, and the baton. I enjoyed the fun cast party, after the show. And, I faced the reality of engineering school. Academic probation. One more year. I had to buckle down.

At that juncture, at a pivotal time, this young man struggled with his identity. Over the summer, I patrolled the campus in my Vanderbilt Security uniform, living off campus in a sub-leased second-floor home apartment.

I was alone. I was unsure. One more year, and I would be searching for that first job. Was engineering my future? Was I really a musician? Once that year I called my single mother to share my plan to hit the road with my band, I guess hoping she would give a blessing. Instead, she dropped everything she was doing, drove three hours to Nashville, and we had a nice conversation over dinner.

Looking back, now, after over thirty eight years of engineering, I realize the magnitude of my decision. It wasn’t really a decision, I guess, more of a passive acceptance of the chosen course of education. I graduated, found my way to a first job, and in several companies have enjoyed a few personal triumphs of mechanical design. I am truly an engineer. The aptitude test was right. I do things like an engineer. I have been cursed or blessed with the quest for precision and particularity an engineer desires in all aspects of life.

Even so, I have never left my music. I have dabbled in bands since college, at church, and in other social settings. Most often these bands are like the college Dixieland band, a few friends, quasi-friends, who put up with each other long enough to do a show or two. Every once in a while, I get to be on stage at a big show with a real audience. It’s fun. It at times is even joyful. At those moments, I realize the magnitude of my decision to remain an engineer.

I almost left Vanderbilt to travel the country with a Dixieland band in a clapped out Chevy van. Instead, I found a job wearing a white shirt and tie, complete with a pocket protector filled with mechanical pencils and pens. I began my career at Robertshaw Controls in 1984, and really did wear a shirt with a pocket protector. Made perfect sense at the time. I have always worked for a company that was decades old, with a proven business model and excellent benefits. I carried my cornet and violin and guitar with me every step of the way, but they most often gather dust in a closet or on a shelf.

My childhood friend traded security for freedom. I traded freedom for security. I traded artistry for designing vehicle engine components and air conditioning compressors. I traded music for musings about cause and effect in quality management and process improvement efforts at retailers. Did I make the right choice?

Over the past few years, I tried my hand at music again. I was asked to be in a pickup band, called “The Gospel G-men.” There, with four men who knew every song, by heart, I tried to fit in with their vision of each song. Some songs needed a fiddle intro, which I couldn’t seem to grasp, and at one and only one performance I failed miserably to create that lead line. That band dissolved, but the performance shortfall remained a strong memory.

I was invited to be in a country gospel band, and made a decent go at it, for a few months. With a repetitive playlist, and a lead guitar vocalist who needed everything to be the same, I was able to bring some lead breaks to the songs. But, in time, the relationships between the band members reached a breaking point, and the band folded.

I tried to be in a bluegrass band, at a local venue, with a “house band.” Nothing like standing on stage and having someone point your direction for a lead break on a song you have only heard for the previous 32 bars. All the while another fiddle player tries to jump in and play something on top of you. I tried to be in another bluegrass band, where charts were available, and realized after a major show in town that I wasn’t really a fiddler. Continued gentle suggestions to go online for lessons, or to attend a fiddler’s convention pointed out the difference between what I do and what the band needed. I left the stage in shame one evening, and drove home from Mechanicsville hoping never to be remembered.

A local Celtic band lost their fiddler, and they remembered that I played violin. Graciously they allowed me to experiment with the charts, but talk about mental chaos. Four different time signatures, at least. Various dances that defined the sonic nature of the songs. And, a prescribed fiddle style, that I again didn’t possess. I couldn’t even get all the charts straight in my head, when I was told I wasn’t really a Celtic fiddler and that was what they needed. Hours of work, helping with the sound system at gigs, finding a sound engineer to ease the band burden, storing the equipment at my house…all for naught.

Recently, I had occasion to explore yet another band opportunity. With some gusto, I gathered the band songs on a playlist, listened to those 50 songs over and over again, played along with them for some hours, and spent time with the band at a couple of get acquainted rehearsals. Great songs. Men of similar life stage, and quite good at their musical craft. I managed to join in with a few measures of string sounds, and all seemed well. But, then the magnitude of the events hit me. Rehearsals, and gigs. Real gigs. All over Richmond, from church to country club to bar. The band, thought to be a stable group, lost the key lead guitarist to a job change, changing the entire soundstage. Carrying the lead lines on a violin became a distinct possibility.

Fear set in, rather quickly. Playing at home, along with recorded music, it is easy to think you have it. But, in the real world, that squeaky tone is magnified by the amplification and speakers on either side of the stage. Could I really play “Blackwater” by the Doobie Brothers? Moreover, could I flex and handle the reality of performing on stage?

Who wouldn’t want to be on stage, entertaining a few dozen people enjoying a brew? Who wouldn’t want to be energized by the chance to just do something on stage, to fit in that moment with some offering that might make sense? Who wouldn’t want to try their best, and to relish that moment in the bright lights?

I’m not sure. For now, though, the chance to go beyond my fear has evaporated with the feelings of shame and sadness. Life goes on, but what at what cost? What did I lose, in avoiding a failure that I alone judge myself to be?

Each attempt to be in a band is like me running a lap around the audience in “Le Marathon.” I grow tired of the distance. I pause from time to time on stage, to wonder aloud about my life. I grow tired with each trial. It is easier to avoid the opportunities, yet with each squandered attempt, the finish line remains far away. I may never cross it.